Abstract:

The purpose of this paper is to look at the emphasis placed on curricular competencies and content within the context of Language Arts 5/6 and Math 5/6 in my classroom. I will be looking at data from my students’ digital portfolio-SpacesEDU- to examine the potential patterns when tagging curricular outcomes in activities created within the app. Specifically, I would like to determine whether curricular competencies or content is featured more prominently in assigned activities across these two subjects in my split 5/6 class.

Using a primarily descriptive approach to the analysis of my quantitative data, I will be looking at the distribution and frequency of tagged curricular outcomes in both math and language arts. I question whether I prioritize competencies or content over the other between the two subjects. My initial assumption is that I tag the curricular competencies more for language arts and the content more in math based on the emphasis and value placed on each within the two curriculums.

This paper will also examine the implications of my finding for my teaching practice and the learning context in my classroom. Determining whether there is a focus on curricular competencies or content could provide valuable insight into the skills I am choosing to highlight and possible teaching interventions. It could also shift the pedagogical approach I take to program planning in the future by allowing me to make informed decisions aimed at improving student outcomes and enhancing my language arts and math instruction.

Introduction:

British’s Columbia’s curriculums for Language Arts 5 & 6 and Math 5 & 6 blend big ideas, curricular competencies, and content to provide depth and scope to learning experiences. The big ideas are the understanding that students are expected to have, but my inquiry looks deeper into the curricular competencies and content sections of each subject curriculum, which focuses on the skills and knowledge they are expected to acquire. As I practice competency-based teaching and assessment in my classroom, I chose these elements of the curriculum to look at more critically because they have different areas of emphasis, one is focused on process while the other is focused on knowledge. This enables me to examine the distinct processes through which students learn and develop skills, separate from the content and knowledge they are acquiring. Of course, in the classroom these concepts are entwined, but for the purpose of this paper, I wanted to determine where I was placing emphasis in each subject. I have also included the Big Ideas in my data although they were not the focus of my inquiry as the concepts are often duplicated in the other two elements as students develop understanding.

“Curricular Competencies are the skills, strategies, and processes that students develop over time. They reflect the ‘Do’ in the Know-Do-Understand model of curriculum. The Curricular Competencies are built on the Thinking, Communicating, and Personal and Social competencies relevant to disciplines that make up an area of learning.”(BC’s Redesigned Curriculum, n.d.) These competencies are often transferable skills that can be applied across curriculums and emphasize critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creativity, and higher-level thinking skills. They also guide how students will apply their understanding, solve problems, and engage in inquiry-based learning. They are about the process of learning and not just the end product.

In Math 5 & 6, the curricular competencies focus on the following strands: Reasoning and Analyzing, Understanding and Solving, Communication and Representing, and Connecting and Reflecting. (Math K-9 Curricular Competencies, n.d.) The curricular competencies for Language Arts 5 & 6 focus on: Comprehend and Connect (reading, listening, viewing), and Create and Communicate (writing, speaking, representing). (English Language Arts Introduction | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, n.d.) What intrigues me about these competencies is the ability to use them to differentiate based on students’ needs. Most students can engage in the procedural aspects of math or language arts, even if the content they are using to demonstrate their learning is not at grade level.

The content in the Language Arts curriculum flows from grade to grade and feels similar to the curricular competencies in that they remain quite general. They include Story/Text, Strategies and Processes, and Language Feature, Structures, and Conventions. (English Language Arts Introduction | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, n.d.) The content remains broad and oftentimes strategy based, and teachers can select specific content that will meet the needs of their learners. The content in Math 5 & 6 builds on previous years but includes grade specific content. It is expansive and varied and is not grouped into headings like the other subjects.

In my practice, I use digital portfolios to collect and assess student work. This also provides me with data relating to student and class proficiency in subject specific competencies. SpacesEDU (which will be referred to as Spaces throughout this paper) is a “digital portfolio and proficiency-based assessment platform built to showcase growth” (Spaces, 2022). I began using it in September 2022 during it’s first year launched. In March of 2024, I was named “Top SpacesEDU User in North America” which I mention only to establish my credentials as a verified and committed user who has significant information to support the inquiry I have created. Spaces has several significant features that allow teachers to: create an engaging digital learning environment, foster empowered learning opportunities, promote visible & continuous assessment, align with evidence-based reporting, and build communities of learning. (Spaces, 2022) Students upload all of their work to the platform digitally where it is assessed in their personal Work Space. In our community spaces, they can comment on multi-media posts that I present to the group. We also share pictures and videos of class activities and events that we participate in.

However, the feature that I appreciated most in this inquiry was its ability to showcase which outcomes I tag for assessment in each subject. Spaces is tied to the new curriculum in British Columbia and is based on the new reporting order where competency-based assessment is prioritized. Competency-based assessment evaluates a student’s proficiency and mastery of specific skills (curricular competencies) and knowledge (content). Each time I create an activity within the app, which is where all my assessment takes place, I tag the competencies and content through which students can demonstrate proficiency by completing the activity. Each activity assesses students on these competencies individually, representing the skills and knowledge they have demonstrated. My dashboard allows me to track this information on students individually or generally as a class, which is what I’ve done for this inquiry.

Inquiry

The purpose of this inquiry is to determine whether the curricular competencies or content is featured more prominently in assigned activities across two subjects, Math and Language Arts, in my split 5/6 class. Before analyzing my data, I initially believed that I utilized the curricular competencies more in Language Arts because they are the pathways for comprehending content. These are the essential skills required for proficiency in language arts. I further suspect that in Math, the reverse was true. I believed I used the curricular competencies to expand on or clarify the content while maintaining a focus on subject matter. While these may sound similar, the intent was different.

Competency-based teaching is often referred to as standards-based instruction in the literature. While the two terms are not interchangeable per se, I will be using the term “competency-based” because our learning standards in BC are called competencies. Using competency-based instruction and assessment in my classroom has already changed my practice. I now align all activities to the curriculum and assess proficiency based on those learning outcomes. This also means that I’ve had to redesign all my rubrics and co-create proficiency criteria for my most used competencies. I have used Shannon Schinkel’s work on proficiency scales to guide this process. (Embrace the Messy!, 2024) This will be ongoing over the next several years.

The next step in my evolution is to determine what I’m assessing. While the curricular competencies and the content are inherently interconnected, where we place our focus can make a difference to student understanding of what we are trying to teach. In recent years, students have been coming into the intermediate grades with fewer skills in both math and language arts. Their ability to write is more limited and their numeracy skills are less developed than in previous years. This is a focus of both our school and the district. My intent with this inquiry is to determine where I’m placing emphasis when assessing proficiency and to determine how I need to adapt to meet student learning needs.

Literature Overview:

In 2016, British Columbia launched its new curriculum, which shifted from a content-based model to a focus on competencies. However, the redesign itself began many years prior. As early as 2012, the Ministry of Education produced a paper titled Enabling Innovation: Transforming Curriculum and Assessment which outlined the key components of the redesign. This paper identified several Guidelines for Curriculum Development which included, “Learning Standards: Provincial curricula should continue to mandate learning standards—what students are expected to know, understand, and be able to do. These learning standards should be fewer than prescribed in the current curriculum, rigorous, and they should emphasize higher order concepts over facts to enable deeper learning and understanding.”(BC’s Redesigned Curriculum, 2012) This reference to learning standards became the basis of the three elements of curriculum in the new curriculum. The new curriculum model is based on three elements that teachers can combine with autonomy to personalize the learning in their classrooms. These three elements, defined in the Orientation Guide, are:

Content- what students are expected to know;

Curricular Competencies- what students are expected to do; and

Big Ideas- what students are expected to understand. (BC’s Redesigned Curriculum, 2016.)

“The Ministry identified this approach as focusing on ‘what students are expected to know, understand and be able to do’ … this ‘know-understand-do’ model set the terms for curriculum work going forward. (Gacoin, 2018) Though not explicitly stated in Ministry documents, this approach seems to be based on, or supported by, the work of Erickson and Lanning regarding concept-based instruction and assessment. Erickson and Lanning argued that the “content coverage model has critical flaws… fails to align with brain research… and assumes that teaching factual knowledge and skills will result in deeper understanding of the concepts, generalizations, and principles that structure a discipline.” (Erickson & Lanning, 2013)

These ideas align with the distinction in the redesigned curriculum between the curricular competencies and the content. Erickson and Lanning built on the ideas of Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) by stating that, “by separating factual knowledge from conceptual knowledge we highlight the need for educators to teach for deeper understanding of conceptual knowledge not just for remembering isolated and small bits of factual knowledge.” (Erickson & Lanning, 2013) Curricular competencies represent the conceptual knowledge, while the content competencies represent the factual knowledge.

In 2013, when British Columbia teachers joined the teams for curriculum redesign, they were provided with the framework and asked to design the new curriculum within that framework. Many teachers expressed concerns that they did not know where the framework had come from and what research it was based up. “Alongside these concerns is the question as to what extent the process of curriculum revisions in BC has actually aligned with a concept-based model of curriculum design, particularly in terms of (a) how a teachable curriculum is developed, (b) implications for assessment, and (c) the explicit assumption that curricular change requires pedagogical change.” (Gacoin, 2018) The concerns of these teachers were well warranted. Although the elementary curriculum was adopted in 2016 (in my school we started using it earlier as part of the pilot program and continued to use it when the launch was bumped due to job action), the new reporting order, which changed the way we assess the new curriculum, only became active in August, 2023.

This belief that the redesigned curriculum would require a pedagogical shift in the way we think about education was a concern to the teacher curriculum development teams, “Because, the curriculum, to work well, it- there needs to be a shift in pedagogy, but we can’t mandate pedagogy.”(Gacoin, 2018) Even as I began to dive into the curriculum, I have been working with for almost ten years, it is apparent to me that using this curriculum effectively means fundamentally changing the way I teach and assess student work. “The implicit assumption that concept-based curriculum will necessitate pedagogical change for many teachers. In other words, the ‘paradigm shift’ for teachers is not only about understanding what the concept-based model is. In working with a concept-based curriculum, a teacher is expected to take up ‘concept-based instruction’ (Erickson & Fanning, 2014, p. 59). (Gacoin, 2018) The Ministry of Education documents have been my primary source of information for this inquiry. The history of the redesign gave me much more information about the intended use of all elements of the curriculum that will likely be part of further research for me. There is not a lot of research looking at the use of curricular competencies verses content because the focus on the redesigned curriculum was to include the third element of the curriculum, the Big Ideas. My inquiry focused on the two assessment of learning aspects, and less on the assessment of understanding.

Research Method:

I teach a grade 5/6 intermediate class in a small, rural community. There are approximately 160 students in our K-6 school. Most of our classes are split grades, including another 5/6 classroom. I currently teach twenty-four students, although one is on a completely independent program and will not be included in the data for this inquiry. I will be looking at data from twenty-three individual portfolios, where students upload and publish all work for assessment. We use the platform Spaces. Most of this is individual work, but some work has also been done in partners or small groups. Assignments include written text, visual representations, photographic captures, and video and audio recordings. Although the sample size is small, it represents the class I am committed to this year and their work between September 2023 and March 2024.

Available as part of my teacher account is the proficiency report feature, which allows me to see individual and class proficiency in each of the curricular competencies and content that I have tagged in activities. I also have a proficiency slider at the top of my app and along the side of my desktop version of the platform which allows me to visually see how many times each competency has been tagged and the overall proficiency of my class as an average. The data is not organized by subject in the slider however, so I copied each data set down from the slider into my notebook. Students have access to their own individual proficiency slider in their version of the application. To protect my student’s data, I will only be analyzing how often I tagged different competencies and not the proficiency that was achieved, either individually or as a class, on those competencies.

Data & Analysis:

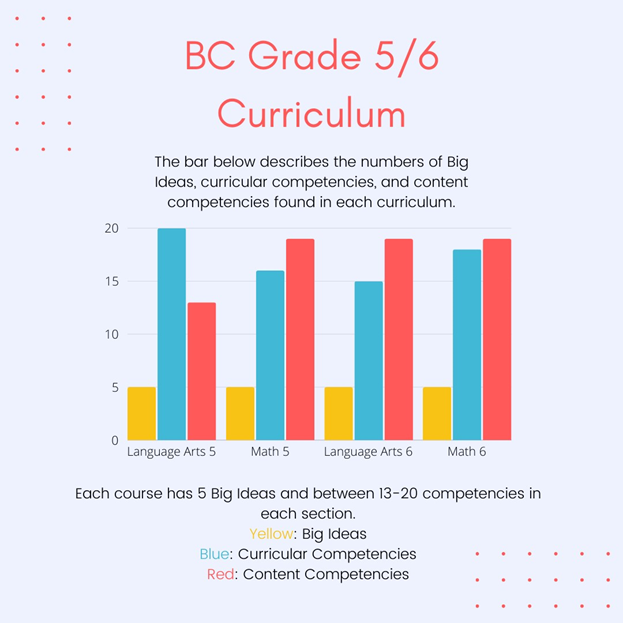

FIGURE 1. This graph visually represents the number of Big Ideas, Curricular Competencies, and Content Competencies found in each of the subject grade levels.

As shown in Figure 1, both Language Arts 5 & 6 and Math 5 & 6 have a set number of Big Ideas, Curricular Competencies, and Content Competencies. Both subjects, across all grade levels, have five Big Ideas. These are the concepts that students are expected to understand throughout the course. The curricular competencies and content competencies do not have a common number. The curricular competencies are what students are expected to be able to do and the content is what students are expected to know.

In grade five Language Arts, there are twenty curricular competencies and thirteen content competencies. In grade six, in the same subject, there are nineteen curricular competencies and fifteen content competencies. While numerous competencies overlap between the grade five and six levels, the variation in language distinguishes the depth of understanding required for proficiency. For example, in the grade 5 ELA (English Language Arts) curriculum, the first curricular competency reads, “Access information from a variety of sources and from prior knowledge to build understanding.” The grade six curriculum states, “Access information and ideas for diverse purposes and from a variety of sources and evaluate their relevance, accuracy, and reliability.” (English Language Arts | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, 2016.) Similarly, in the content section, almost all the competencies are the same with the exception of two new competencies at the grade six level and a distinction between one. At the grade five level, students are expected to know about point of view, while at the grade six level, they expand on this knowledge and apply techniques of persuasion. (English Language Arts | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, 2016.) This makes ELA easy to teach in a split grade.

In Math five, there are sixteen curricular competencies and nineteen content competencies. In grade six, there are eighteen curricular competencies and nineteen content competencies. These two grades have ten common curricular competencies, verbatim. The remaining ones are distinct. Correspondingly, the content competencies are quite different. While they have similar themes, the content is unique to each grade in either subject or depth. Clearly the sixth-grade competencies build on those mastered on grade five. Math is not as easy to teach in a split class as eventually, you must group for grade level on content.

FIGURE 2. This graph represents the number of times each type of competency was tagged in math and language arts, across two grade levels.

Figure 2 shows how many times each type of competency was tagged in the assessment of student work. What caught my attention immediately was the frequency of curricular competencies across three out of the four courses. Math 6 was the only course in which content competencies outnumbered the curricular competencies. While this reinforced my initial assumptions, it only partially illustrated the situation- which I will delve into later.

The Language Arts 5 course affirmed my initial expectation that I would evaluate a greater number of curricular competencies compared to content. I have not tagged any of the ELA 5 Big Ideas, which did surprise me. Six of twenty curricular competencies were tagged a total of 216 times which represented 90% of the tags in this subject. Only three of the thirteen content competencies were tagged 45 times which made up the other 10%.

The Language Arts 6 curriculum also confirmed my assumption that more curricular competencies would be tagged but this course was much more actively used for assessment of all students. All five of the Big Ideas were tagged 741 times in total. These ranged from 63 tags to 288 tags, depending on the Big Idea. Tags of Big Ideas made up 24% of the total tags for ELA 6 which was more significant than I expected. Fifteen of the nineteen curricular competencies were tagged a total of 1870 times. This represented 60% of the total tags for ELA. Additionally, 80% of the curricular competencies for this course have already been tagged and therefore assessed in the first two terms of the school year. Ten of fifteen content competencies were tagged for assessment 501 times. This represents 16% of the total tagged assessments in ELA 6 and 67% of the curriculum content in total.

The outcomes in Math 5 mirrored those in the Language Arts curriculums, contrary to my expectation. I had initially believed that content competencies would play a more significant role in my assessment of the curriculum; however, curricular competencies outnumbered the content by a considerable margin. Only one of the Big Ideas in this curriculum was tagged, 189 times. This accounted for 11% of total assessed tags in Math 5. Thirteen of the sixteen curricular competencies were tagged 1370 times. 81% of the curricular competencies for Math 5 have been tagged in the first six months of the school year. The curricular competencies represented 79% of the assessed tags for Math 5 in this inquiry. Only three of the content competencies were tagged, which represents 16% of the total content curriculum. This number was much lower than I expected considering the considerable review and focus we put into Math 5 concepts. Content was tagged 178 times for a total of 10% of the assessed tags in Math 5.

The Math 6 curriculum presented the most surprising findings. Initially it seemed to align with my expectations by featuring more content than curricular competencies. Seven of eighteen curricular competencies were tagged which represented 39% of the total tags for this course. These were tagged 488 times. This data also indicated that 39% of all curricular competencies in Math 6 have been assessed. In the content section, only three of nineteen competencies were tagged, which was unexpected. However, these three were tagged 752 times. More significantly, one content area was tagged for assessment 677 times on its own. These three content competencies accounted for 61% of assessed tags but only represented 16% of the content for this curriculum. In this course, I did not tag any of the Big Ideas.

This data gave me a lot of opportunities for reflection. The first thing that became apparent to me is that in my split 5/6 class, I do not evenly distribute the outcomes I tag between the two grade levels. Using competency-based instruction and assessment I have been becoming increasingly familiar with the standards of each curriculum because I must choose what to tag in every activity I assess. Only as I began investigating this data have a realized how different the curriculums are between grade levels. The curricular competencies seem to be the bridge between grade levels to develop literacy and numeracy skills. My belief was that they transcended grade levels, but I am questioning that now. They have similar themes but are different enough that I fear I might be missing important academic steps in the development of student understanding. I am questioning whether I should create activities with different assessment tags for each grade or whether the common sub-headings of the curricular competencies are enough to justify my combined grade activities.

I also notice that in Language Arts, I tend to tag grade six competencies more, while in Math, I focus on the grade five curriculum. The grade 5 and 6 ELA curriculums are very similar in their content and relatively similar in the curricular competencies so this does not seem to be an issue; however, I should remember to differentiate my assessment practices so that the higher-level competencies do not adversely affect my younger learners. We invested significant time in cross-curricular TED talks recently, and presentation skills are a grade six competency while features of oral language are featured in the grade five curriculum. This also may have impacted my decision to tag more of the grade six ELA outcomes. In Math, the prevalence of grade five outcomes reflects the numeracy skills of most my students. As a class, we often practice with the grade five outcomes as a group and then I pull the grade sixes for additional content. The grade sixes account for tags in both curriculums while the grade fives are generally only assessed on grade five curriculum.

What concerns me more is the absence of tags regarding the Big Ideas in both math curriculums. The Big Ideas represent the “understand” in the curriculum elements. I will need to examine whether this reflects a lack of their understanding, an oversight on my part when tagging, or a lack of coverage of the Big Ideas in my instruction.

The results of all this data intrigued me, prompting me to explore which of the tags were used most frequently in my assessment practices.

FIGURE 3. This graph represents the top three most tagged learning standards in each category in the Math 5 curriculum.

This graph directly reflects the focus of my instruction in the second term of the year but surprised me with what it did not show. The only Big Idea we tagged for assessment was, “Numbers can describe quantities that can be represented by equivalent fractions.” (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, n.d.) This has been an instructional focus since the Winter Break so that was to be expected. This directly relates to two of the content competencies that were also predominantly tagged: equivalent fractions and multiplication and division facts to 100. (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, n.d.) Both of these content areas are prerequisite skills for understanding fractions. The third most commonly tagged content competency was, “Number Concepts to 1 000 000” (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, n.d.) This is a concept I always cover at the beginning of each school year to ensure student understanding of number. It includes place value, counting strategies including multiples and skip counting, and comparing and ordering numbers. Finally, I examined the most tagged curricular competencies. This included, “Using reasoning to explore and make connections,” (Math K-9 Curricular Competencies, n.d.) which was tagged almost three times as often as any of the content competencies. This competency is used when I want to assess whether students can connect their current learning to previous learning. It is also applied when students are working on word problems or inquiry-based math activities. As we worked on reflective math practices, “Explain and justify mathematical decisions and ideas” (Math K-9 Curricular Competencies, n.d.) was also tagged several times, 198 to be exact. Finally, the curricular competency that focuses on visualization was tagged 142 times. This made sense to me because we often draw out, or visualize, fractions using a variety of methods and by grade five, students are attempting to make these visualizations more internal.

FIGURE 4. This graph represents the top three most tagged learning standards in each category in the Math 6 curriculum.

Although this data supported my original thinking, that content would be more prevalent in math assessment, what struck me most was the dominance of one tagged content competency that skewed the results from the consistency of the other three data sets. The outcome, “Multiplication and division facts to 100” was tagged 677 times, which is more than double any other competency in the Math 6 curriculum. In fact, it was more than double of any other tagged competency in every other course. This is the result of two separate Multiplication Blitz interventions that we did as a class this year, once in October 2023 and once in February 2024. Without fluency in this skill, students were unable to demonstrate proficiency with other competencies. Without this outlier data, this graph would also show the predominance of curricular competencies in Math 6. Oddly, the curricular competencies most tagged in Math 6 were different than the curricular competencies tagged most in Math 5. Here, students were assessed on using mathematical vocabulary, applying multiple strategies to solve problems, and demonstrating mental math strategies- though these competencies were also tagged in the grade 5 curriculum where found. (Math K-9 Curricular Competencies, 2016.) Combined, these competencies would be more profound. I now question whether there is a better way to track which common competencies I tag for more accurate data.

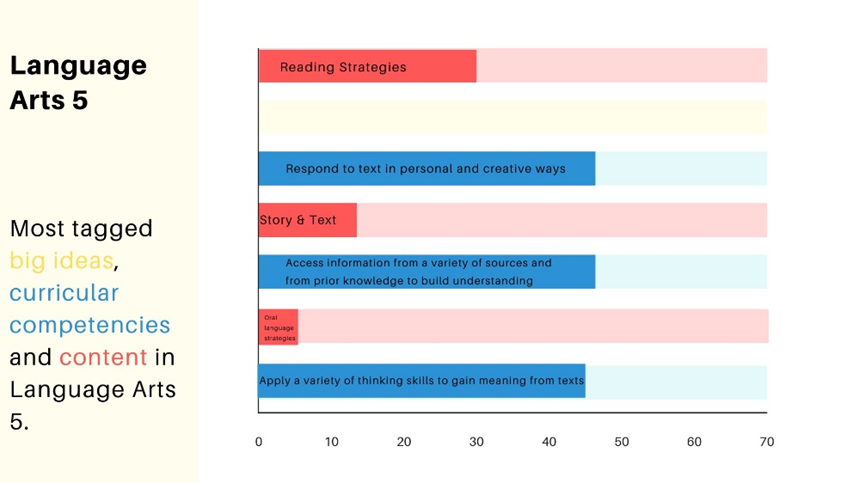

FIGURE 5. This graph represents the top three most tagged learning standards in each category in the ELA 5 curriculum.

My assessment of the ELA 5 curriculum met my initial expectations. Curricular competencies have clearly been evaluated more often than content. I was unsurprised that reading strategies, story and text, and oral language strategies were the most tagged content competencies as these outcomes make up the basis of our learning in language arts. Reading strategies are essential skills for all students to have across all subject areas so we spend quite a bit of time working on them. These include skills like summarizing, paraphrasing, inferring, visualizing, and making connections. Story and text competencies include text features and forms which not only support students’ understanding of how to read text, but it also supports their written work. This understanding also helps them interpret non-fiction writing by exposing them to literary devices and elements, which were tagged during our short story and poetry units. Finally, the frequency of the curricular competencies provides evidence of the effort students have put into their comprehension and responses to literature and text. “Access information and ideas from a variety of sources and from prior knowledge to build understanding” and “Apply a variety of thinking skills to gain meaning from texts” (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, 2016.) are both comprehension based strategies that allow students to access and apply information from texts. The final of the top three curricular competencies, “Respond to text in personal and creative ways,” (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, 2016.) allows students to apply their learning. They can make connections and be creative in their interpretation and application of information and skill. This was used in many ways. At times, students expressed their understanding through written response, while on other occasions, they used audio or video aids to communicate their learning to Spaces for assessment. The use of this platform allows them to showcase their skills from a perspective that emphasizes their strengths.

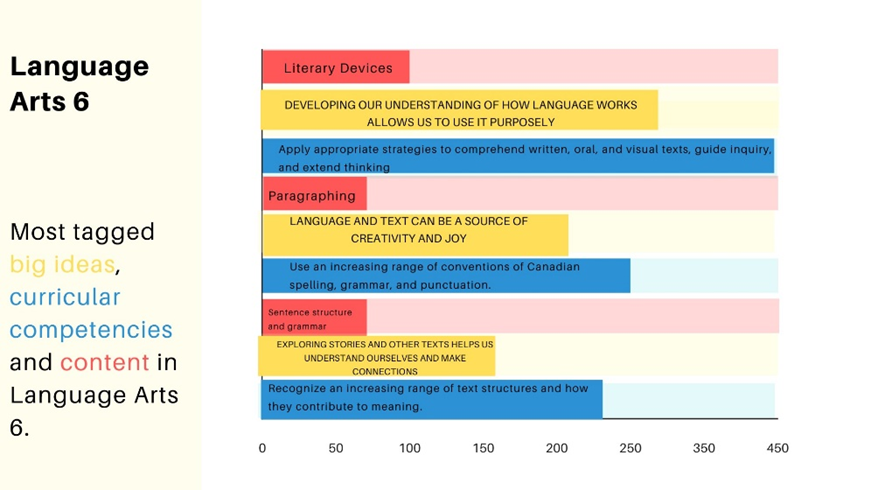

FIGURE 6. This graph represents the top three most tagged learning standards in each category in the ELA 6 curriculum.

This graph accurately reflects the teaching and learning that has been happening in my class. The paragraphing and sentence structure and grammar in the content competencies demonstrates how much work we’ve been putting into our writing. The literary devices content tags tell the story of our poetry unit and the time we took to play with figurative language. The curricular competencies all showcase the work that we have put into our reading and writing practices of understanding and then applying the skills we have learned. Even the Big Ideas were strategically applied and represent the learning that took place. You can see how the content was applied using the curricular competencies and then understanding was shown in the frequency of the Big Idea tags.

Not only did using Spaces provide me with the data I have been exploring in this inquiry, but it also provided the opportunity to share this learning with students and their families in a meaningful way. Using Spaces allows us to take a Big Idea like, “Language can be a source of creativity and joy” (Curriculum | Building Student Success – B.C. Curriculum, 2016.) and make it visible. What does “joy” look like? It is such a subjective term that is difficult to assess until you can see it in a video or hear it in an audio recording. The features of Spaces also provide a platform to see the competencies in action. It is difficult to see a mental math strategy on a worksheet but much easier to see it in a video. This data therefore becomes more relevant to families because they can see learning and assessment and have a greater understanding of what we are learning and how the curriculum is being applied. Another area for study might be whether I assess some of the competencies more because they are accessible through Spaces.

Conclusion:

My data for this inquiry has given me a lot to think about. I can see now that I do prioritize the process that the curricular competencies provide. I can see that I am asking my students to do more than learn content, I am teaching them how to be thinkers and doers. I can see that what we have been doing is on the right track, even where I thought my pedagogy was going to diverge from my practice. But its just a start. There is so much more we can do. For example, I would like to start integrating the Big Ideas into both my formative and summative assessments. I would like students to understand that the Big Ideas are the purpose of what we are doing and that the competencies (both curricular and content) are how we get there. I would like my students to start using their own proficiency sliders to determine where they need to put their efforts. This metacognition would allow them the autonomy to make choices about their learning. My class last year understood this, but my current class does not yet. I would like to look at the competencies that I’ve overlooked so far and determine a way to integrate them into my instruction. I want to look at the proficiency levels of my students to see if there is a relationship between proficiency and the number of times we have tagged an outcome. I can also see that to cover the content effectively, I must focus on the curricular competencies. They will allow me to differentiate and personalize the learning for my students.

Looking in the documents provided by the Ministry of Education has also triggered a lot of reflection about things that are not covered in this inquiry. The core competencies, which have always been superficial hoop jumping to me, are now intriguing based on reading I have done. I am also interested in pursuing which of the competencies are best showcased in a digital portfolio because of the variety of options to demonstrate learning that they provide. Finally, I would be interested in developing a better tracking system to ensure I address as many of the Big Ideas, curricular competencies, and content as possible.

When I began this inquiry, my interest was not in the distinction between curricular competencies and content as much as it was about whether the process of learning or the knowledge was more visible in my assessment practices. Diving into the curriculum and the process of its development has been enlightening and thought provoking. Even though our district participated in the piloting of the curriculum, prior to its launch in 2016, there was so much about it that I did not know or understand. There was no training on this curriculum other than an overview of the changes where teachers were assured, they were already doing this style of teaching. I was not. I did not understand the purpose of the redesign except in broad terms and I have treated some of its most incredible features as hoops I had to jump through. But over the past few years, as I have gotten excited about digital portfolios and competency-based assessments and then instruction, I have started to look more closely at it. A shift in pedagogy is happening for me. The one the teachers worried about mandating back in 2013. I understand its impact now.

Bibliography

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives : complete edition. Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. https://eduq.info/xmlui/handle/11515/18824

BC Ministry of Education. (2012). Enabling Innovation: Transforming curriculum and assessment. Retrieved from https://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/irp/docs/ca_transformation.pdf

BC Ministry of Education. (2013b). Exploring curriculum design: Transforming curriculum and assessment. Retrieved from https:// www.bced.gov.bc.ca/irp/docs/exp_curr_design.pdf

BC Ministry of Education. BC’s Redesigned Curriculum. (n.d.).

BC Ministry of Education. (2016) English Language Arts | Building Student Success—B.C. Curriculum. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts

BC Ministry of Education. (2016) Curriculum | Building Student Success—B.C. Curriculum. (n.d.). Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum

BC Ministry of Education. (2016) English Language Arts Introduction | Building Student Success—B.C. Curriculum. (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2024, from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts/introduction

Erickson, H. L., & Lanning, L. A. (2013). Transitioning to Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction: How to Bring Content and Process Together. Corwin Press.

Erickson, H. L., Lanning, L. A., & French, R. (2017). Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom. Corwin. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506355382

Gacoin, A. (2018). The politics of curriculum making.

Math K-9 Curricular Competencies. (2016).

Peterson, A. (2023). EDUCATION TRANSFORMATION IN BRITISH COLUMBIA.

Schinkel, Shannon. Embrace the Messy! (2024). Embrace the Messy! https://mygrowthmindset.home.blog/

SpacesEDU. (2022). Home. Retrieved from https://spacesedu.com/en/

Leave a Reply