Abstract:

The purpose of this intervention is to increase family engagement with the digital portfolio app SpacesEDU. Families play an important role in the overall success of their student’s education so developing an intervention to teach them how to interact with their student’s learning through the app is beneficial not only to their student, but to the overall success of the portfolios as well. I plan to blend behaviorist, cognitivist, and constructivist learning theories using an action mapping approach. Behaviourist principles will be used to prompt requested behaviours, cognitivist principles to increase understanding, and constructivist principles to promote active engagement. I have created a series of newsletters to educate families about SpacesEDU (which will be referred to as Spaces throughout this essay) and have provided suggestions and activities to help them become active partners in their student’s learning journey. The newsletters will introduce families to the features of Spaces, highlight its benefits, and offer practical engagement strategies. The implementation plan includes a consistent timeline for newsletter rollout, and specific activities to ensure families can apply the knowledge delivered in each issue. Evaluation of this intervention will be conducted through various methods, including usage analytics, completion of activities, and a survey to assess the impact of the intervention and help to determine future supports. This paper, and the intervention itself, offers a coordinated approach to enhance family engagement within Spaces to foster a collaborative relationship between school and home with the collective goal of increasing student success.

Introduction

The essential role that families play in their student’s education is well documented in the literature. Families that are informed and engaged in all aspects of their student’s learning can be an incredible source of support to both the learner and the teacher. In his paper, Parental Engagement: Impacts, Influences, and Resources, Gorman states, “When families and schools are collaborating as partners, parents have the opportunity to feel empowered to advocate for their children and academic achievement among children can increase.” (Gorman, 2021) Parental involvement and engagement in their children’s education extends to a multitude of areas that have a positive impact on student outcomes. Studies show the following benefits to parental engagement in educational activities: children tend to achieve more in all areas; there is an improvement in grades, test scores, and attendance; children consistently complete their homework; children have better self-esteem, are more self-disciplined, show higher aspirations and motivation; and have a positive attitude about school that results in improved behaviours. (Sapungan & Sapungan, 2014)

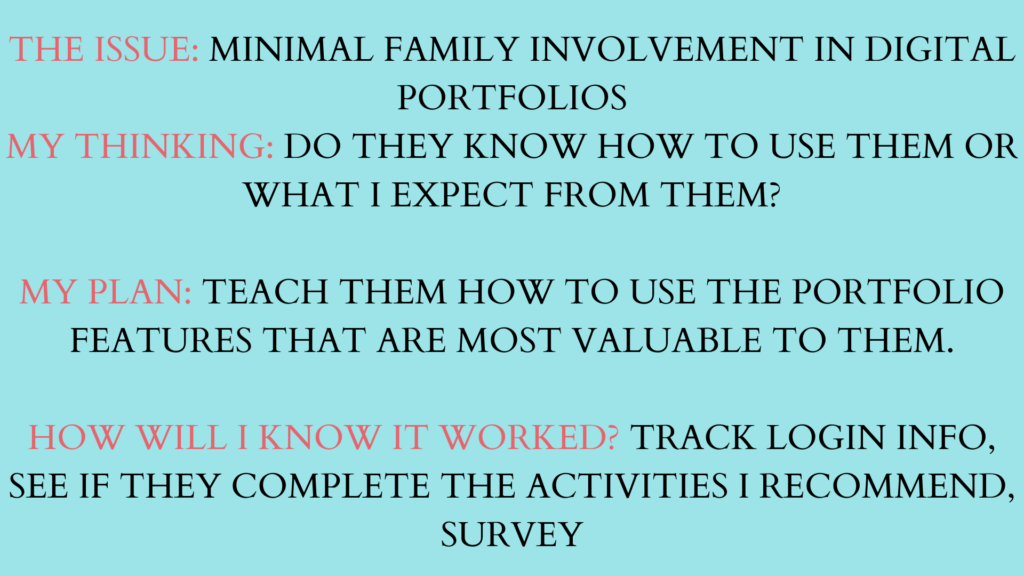

The problem I am attempting to address is that of limited family engagement with students’ Spaces portfolios. Although the value of these portfolios to students, families, and teachers feels transformative to me, I have been unable to elicit the same enthusiasm from families. Oftentimes, families feel the weight of the executive role in their student’s education: paperwork, ensuring work completion, and supporting classroom expectations. “Although parents often want to help their children with school, they do not always possess the time and resources to accomplish these goals.” (Gorman, 2021) Spaces allows us to focus on other avenues of engagement like providing feedback on student’s work, uploading evidence of learning that happens outside of the classroom, and becoming a member of the classroom community. “SpacesEDU is a digital portfolio and proficiency-based assessment platform built to showcase growth.” (Spaces, n.d.) These types of contributions that families make to their students’ learning are frequently underestimated, yet they significantly enhance their students’ sense of support and the value they place on their own work. By teaching families how to engage with their student’s learning through the Spaces app, families will have a better understanding of the work we are doing and their role in that work.

The role that families can play in their student’s Spaces portfolio can include co-facilitator of their student’s learning. In her article, School and Family Connections, Joyce Epstein noted that, “most schools leave it to families to decide whether and how to become involved in their children’s schools…increasingly, schools are…constructing programs to help more families become ‘knowledgeable partners’ in their children’s education.” (Epstein, 1990) She also notes that, “legitimate and comprehensive school and family partnerships should alter the basic roles and behaviours of the average family and change the practices of the typical school.” (Epstein, 1990) A hopeful goal of this intervention is to fundamentally change the way families view their role regarding their student’s learning and therefore engage in a practice that will support their student as a learner.

I will use newsletters as a teaching document in a structured manner to increase family engagement. I have focused my efforts on this intervention plan because it meets the needs of my adult learners by providing relevant, applicable information in small chunks that they can immediately use to engage confidently with the platform. My hope is that providing instruction to my families will result in greater engagement and understanding of my teaching and assessment practices. “Frequent use of parent involvement leads parents to report that they receive more ideas about how to help their children…and that they know more about instructional programs than they did in previous years.” (Anderson, 2008)

Learning Context

The learners are adults who have a diverse skillset regarding technology and a wide range of involvement in their student’s education. Some are eager to explore the platform further, while others perceive it as an additional obligation. At the onset of this intervention, only eighteen of twenty-four families had signed up with the app, and many had not signed on in months. In a parent meeting, one of my families expressed frustration and dislike for the app because they kept getting notifications that they did not want and didn’t know how to determine what was a priority.

I have six families who do not engage in the app at all, including one who has stated that they will not access the app, one with limited internet access, and one who is new to Canada and has moderate English language skills. I have downloaded the newsletters to send home with the first seven families, although they will be unable to access the links. Four of these families have indicated they are getting the emails so I have discontinued sending the newsletter in paper format to those families. Our teacher-librarian, who is also Filipino, has reached out to my newly Canadian family and has shown them the app in a one-on-one meeting. Three of my six absent families have now joined the app.

At the beginning of the school year, I met with parents at our Meet the Teacher night and demonstrated briefly how Spaces works. Eight of my families showed up and we downloaded the app, and I showed them it’s basic features. I also gave them “Family Account” handouts from the company that explained some of the features of the app. As we don’t have regular face to face contact, and I have a consistent group email that goes out, I decided the best way to reach most of them was through the family email updates. I have all my families but one on this email list and they respond when required. This also allows families the autonomy to choose not to engage with the emails and content if they decide not to without pressure from myself or other families. The drawback of email as a primary method of communication is that it is often one way. I have no way to determine if parents are reading the newsletters, or whether they have questions unless they reach out. It’s also difficult to determine if this is valuable information for them unless they offer feedback.

Theoretical Framework: Behaviourism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism

Several aspects of this intervention were based on behaviour learning theories. Included in the newsletters were modelling activities where families could watch videos to see the application of different engagement strategies and could replicate them in their own way. The scaffolded nature of the newsletters also allowed families to build on previously addressed skills which reinforced the concept of repetition in their learning. I also provided feedback where appropriate. As I shared the specific types of interactions and feedback I hoped to see within the portfolios, I essentially guided and shaped their learning experiences. Finally, although less intentional, families were positively rewarded for their contributions and commitment as engagement statistics were included in weekly emails. (Zhou & Brown, 2017)

Cognitivism was also a significant piece of the Spaces intervention. Within the framework of my learning design, I used cognitive learning principles such as attention and focus when designing the newsletters. The information was presented in a colourful and fun way. Short pieces of information were included to capture the attention of the families without overwhelming them. (Ally, 2018) The newsletters and “Try This” activities were interactive and had multi-media elements. The newsletters built upon previous learning which allowed families to retrieve relevant information and apply it in multiple ways over the course of the intervention. Families were taught how to provide feedback to elicit higher level thinking responses which meant that they also needed to be aware of what they were trying to achieve in advance. The structure of the intervention was designed to achieve both basic learning processes such as memory and more intensive learning like critical thing and metacognition. (Zhou & Brown, 2017)

Finally, I applied a constructivist approach to address the “why” of their learning process. Families were asked to actively engage with the platform in several ways and build their understanding of its features with authentic tasks. Each newsletter builds on the skills and knowledge acquired in the previous issues to enrich understanding of the concepts offered. I also added a dedicated Families Space on the platform where they could go for more resources. The intent of this intervention was to allow families to create their own understanding of how the features of Spaces could support their student’s learning, the feedback given to that learning, and how they chose to engage with the platform. I created activities for them to try but it is up to families how they apply those strategies. “The learner is the center of the learning, with the instructor playing an advising and facilitating role.” (Ally, 2008) One of the principles I used as a starting point was that of relevance. All the activities had families engaging with their student’s work or community experiences. Using a constructivist approach, I believed families would become more engaged because the content of the portfolios themselves were relevant to them. It was about their own children. (Zhou & Brown, 2017)

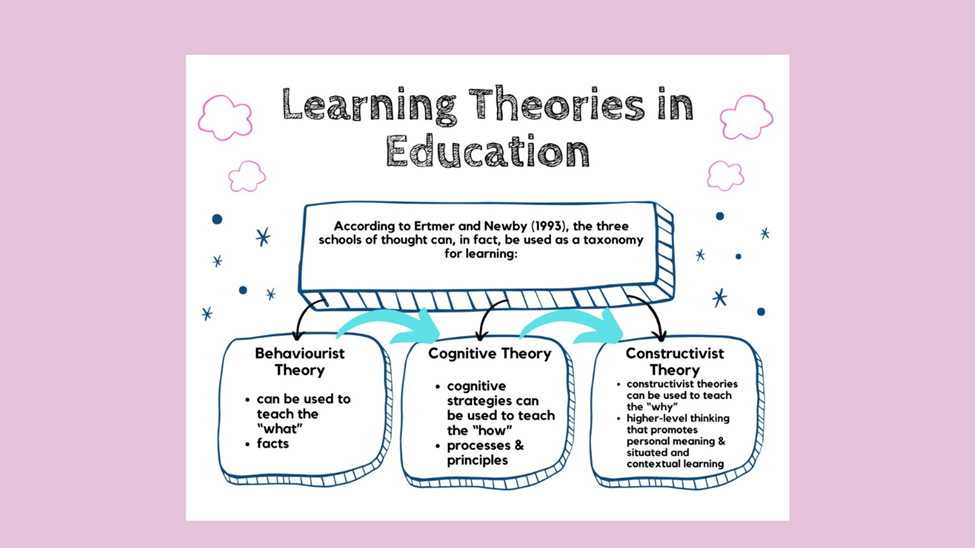

The combination of these three learning theories is well known in the literature. According to Roy, “These theories present a theoretical framework to explain how children learn and how teachers should present information to them.” (Roy, 2020) Though the learners in my intervention were not children, the theories have been adapted in my own learning design.

“According to Ertmer and Newby (1993), the three schools of thought can, in fact, be used as a taxonomy for learning. Behaviorists’ strategies can be used to teach the what (facts); cognitive strategies can be used to teach the how (processes and principles); and constructivist strategies can be used to teach the why (higher-level thinking that promotes personal meaning and situated and contextual learning).” (Ally, 2008) This thinking around taxonomy applied to my intervention as I created activities to promote different types of interactions that families could have with students on the Spaces platform. Not only were the families asked to try activities that prompted thinking that belonged to different learning theories, but they were also designed to promote different levels of thinking in the students as they responded to that feedback.

Figure 4: Visual of learning theory taxonomy suggested by Ertmer & Newby (1993) Created by stephcarpy on Canva.

Learning Design: Action Mapping

I was intrigued by the concept of action mapping as the backbone of my design. The creator, Cathy Moore, claims that “Action Mapping results in real actions, rather than merely delivering information.” (Sengupta, 2020) This concept focuses on four main goals: defining the goal, identifying what people need to do, designing practice activities, and identifying what people need to know.

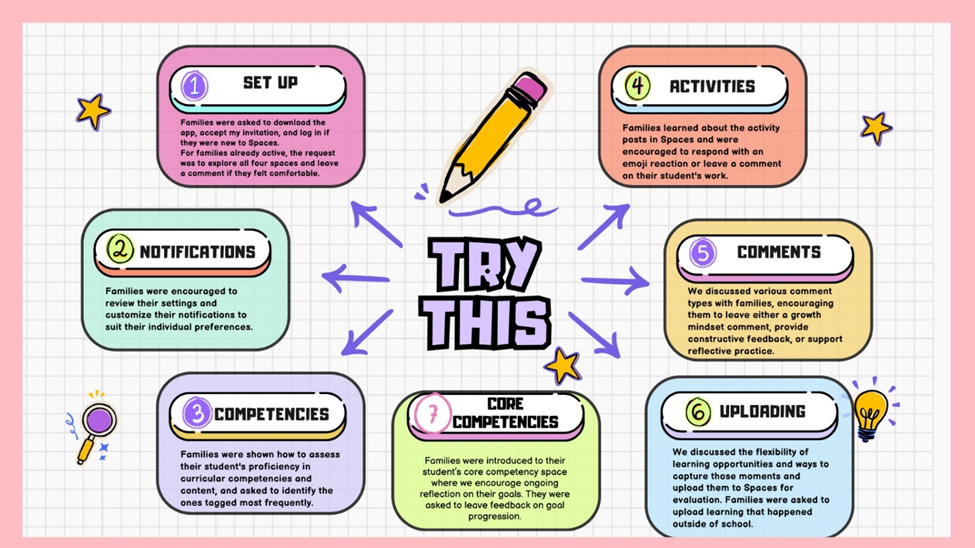

In the Spaces intervention, the goal is to inspire more family engagement with their student’s digital portfolio by teaching them how to interact with the platform and offering suggestions for how they might use it to encourage student growth. A list of essential skills was then identified as the basis for the “Try This” practice activities, which included: downloading the app, discovering basic features, learning how to offer feedback and suggestions for constructive feedback. These skills were filtered for efficacy and only became part of the intervention if they were required for understanding of the portfolio. To avoid overwhelming families with unnecessary details, additional information was provided via links in the newsletters. These included links to the British Columbia curriculum, SpacesEdu resources, and blog posts about standards-based grading practices. The “Try This” practice activities reflected these goals and can be found in figure 5. These activities were designed to showcase application of the essential skills.

Action mapping also promotes the concepts of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Sengupta, 2020). In the Spaces intervention, families can determine which learning activities they participate in, how they choose to respond, and how they engage with the platform, which encourages their autonomy. The newsletters aim to enhance their proficiency so that they are able to navigate the app efficiently but also respond to their student’s work in a way to promote growth. Additionally, families see the relatedness because the subject of the portfolios themselves are their own children or dependents.

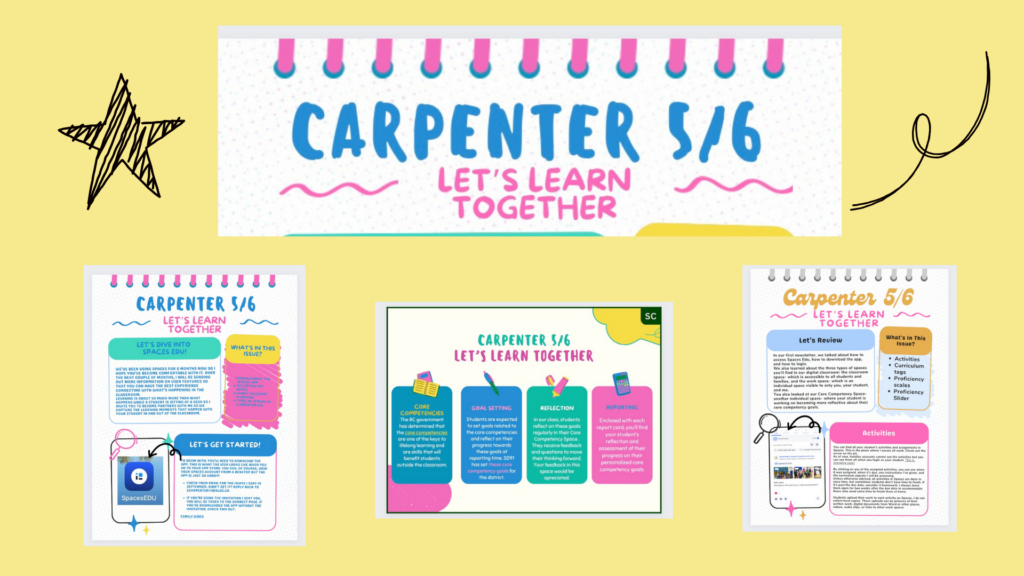

The Intervention: Designing Newsletters for Family Engagement

Newsletter #1: downloading the app, setting up the account, types of spaces.

Newsletter #1B: managing notifications.

Newsletter #2: activities, curriculum tags, proficiency scale, proficiency slider

Newsletter #3: giving feedback, making comments, messaging.

Newsletter #3B: constructive feedback, growth mindset, reflective practice & storytelling

Newsletter #4: how to capture learning that happens outside of the classroom

Newsletter #4B: student core competency goal setting and tracking

To ensure accessibility and inclusivity, these newsletters are distributed through an active email communication system that was previously established. Paper copies were also printed off and sent home with students whose families requested paper copies. This was the case for only one family as most families who have regular access to Spaces and are interested in developing their skills, also have email and internet access. The newsletters have been designed in a chunk format. Each concept is discussed in a short section in user-friendly language. Pictures and videos have been included where appropriate so that visual learners can complete the activity without having to rely solely on the written components of the newsletter.

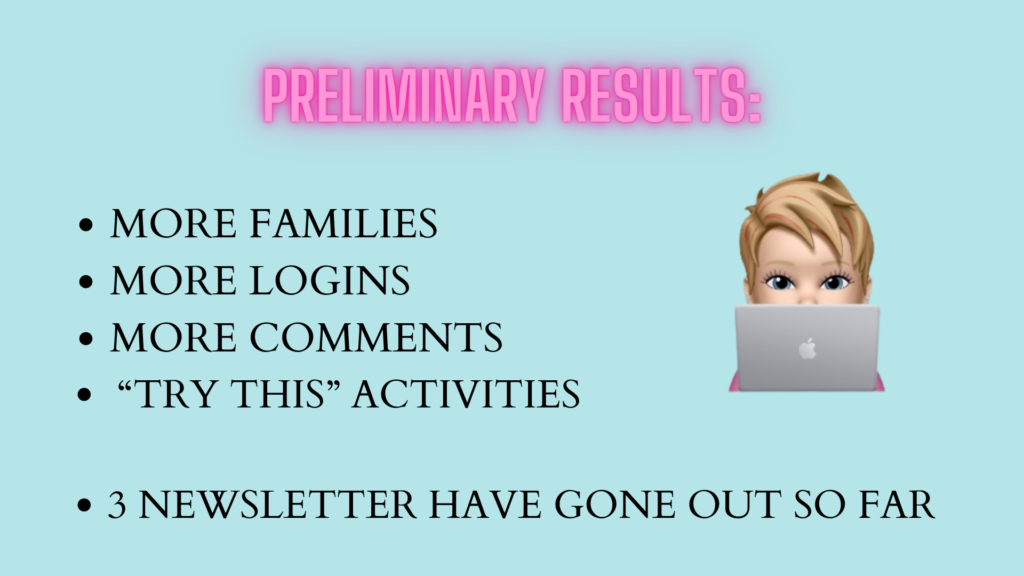

Preliminary Results:

In the first month of my intervention, I have seen significant improvement in family engagement. Four newsletters have been sent out so far. In the first week, three more families signed into their family account and joined the app. This raises my active families from eighteen to twenty-one. All of these families have continued to interact with the platform in various ways. In the past month, there have been eighty-three distinct family logins, and these do not include times families logged in as a student to see the activities space. Twenty-three families have left comments on their student’s work and thirty-one “Try This” activities have been undertaken. Although I was unable to track family usage prior to the intervention- because of app limitations- only eight of my families had a login in February prior to the intervention on February 21st, 2024. Additionally, and possibly unrelated, families have also increased their engagement in the classroom too. My parent-teacher interviews were full, and all positive. Twelve families came out to watch our TED talk presentations last Friday and support their student. Parent volunteering for field trips next month is up as well and in intermediate classes, these can be difficult to facilitate.

Conclusion:

Family engagement is an important part of the education process. “Teachers and parents are believed to share common goals for their children, which can be achieved most effectively when teachers and parents work together.” (Anderson, 2008) This intervention was designed to identify those common goals and apply similar strategies we could use to meet those objectives together. By applying behaviourist principles to encourage parent response to emails, cognitivist principles to create actionable steps for them to take, and constructivist principles to demonstrate relevance and engage them in authentic tasks, the intervention was curated to build on the success that families have already had with their student’s education. The learning design followed a business model- Action Mapping- to encourage immediate results with the least amount of additional work for families. The newsletters provided information specific to our learning context and included a variety of learning activities. The intent, and the preliminary results indicate that family involvement can be encouraged, taught, and ultimately increased.

References

Ally, M. (2008). Foundations of Educational Theory for Online Learning. In T. Anderson (Eds) The Theory and Practice of Online Learning. (pp. 16-44). Athabasca University Press.

Anderson, T. (2008). The Theory and Practice of Online Learning. Athabasca University Press.

Epstein, J. L. (1990). School and Family Connections: Theory, Research, and Implications for Integrating Sociologies of Education and Family. Marriage & Family Review, 15(1–2), 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v15n01_06

Ertmer, P.A., & Newby, T.J., (1993) Behaviorism, cognitivsm, constructivism:

Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective.

Performance Improvement Quarterly, 6 (4), 50-60.

Gorman, S. (2021). Parent Engagement: Impacts, Influences, and Resources.

Moore, C. (n.d.) Action Mapping. Cathy Moore.

Roy, D. (2020). Skinned Knees and ABCs: The Complex World of Schools. Routledge India. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003043201

Sapungan, G., & Sapungan, R. (2014). Parental Involvement in Child’s Education: Importance, Barriers and Benefits. Asian Journal of Management Sciences & Education, Vol.3 No. 2, 42–48.

Sengupta, D. (2020, August 12). How Does Action Mapping Motivate Learners? eLearning Industry. https://elearningindustry.com/how-does-action-mapping-motivate-learners

SpacesEDU. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from https://spacesedu.com/en/

WGU. (2005). What is Behavioral Learning Theory? WGU Blog.

Zhou, Molly and Brown, David, “Educational Learning Theories: 2nd Edition”

(2015) Education Open Textbooks. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/education-textbooks/1

Leave a Reply